Why Saving 10% Isn't Enough

JUST FOLLOWING THE HERD

When meeting new clients and asking them how they are going about their finances, I am surprised at how often people base their decisions on what others are doing. They may something like this: "I read a lot about what might be best for me to do, but it was hard to decide. It seems like most people do _______, so that's what I'm doing."

I've heard that "reasoning" (can you call it that?) for decisions about investment selection, insurance coverage, how much money to save, and countless other financial decisions.

We're social animals, sometimes not unlike the herd-following sheep. That's what the science tells us. We may attempt to make decisions based on our own rationale and analysis of what is best for us, but we are heavily influenced by what we observe in the choices of others.

Instead of being 100% independent thinkers, we form beliefs about how we should do things based on what we perceive to be social norms. Some psychology even suggests we may even feel more comfortable making a wrong decision along with others if it means we all share the negative consequence together, rather than make an individualized decision that's best for ourselves (just google "bandwagon effect" or "conformity" and you'll see what I mean).

So how are we affected by cultural norms toward saving money? More specifically, I'd like to ask: how fast (at what rate) should we be saving our money?

A LOW BAR

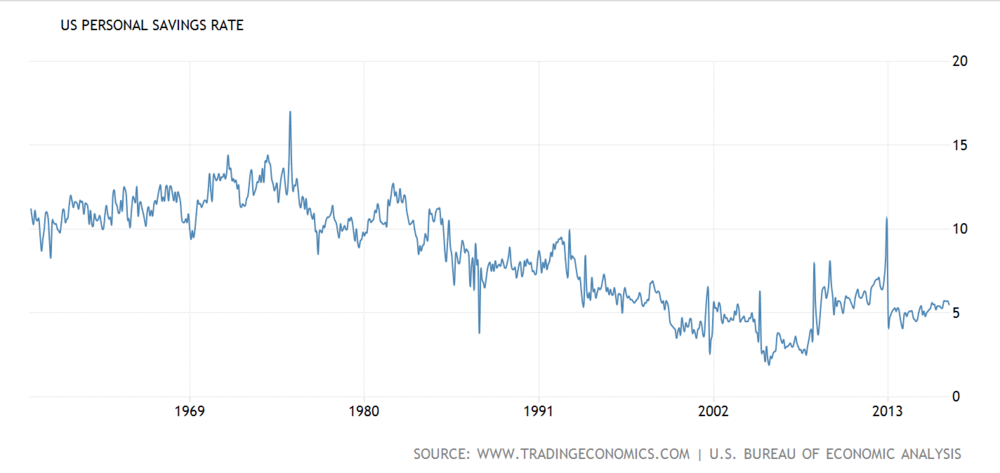

In the U.S., we've set the bar pretty low for ourselves. Or, rather, it's been lowered over time. Up until the mid-1980's, the U.S. personal savings rate was between 10-15%:

In July 2005, it was as low as 1.9%, and by one measure it's even estimated that the personal savings rate in 2005 for Americans was negative.

In late 2016, the household savings rate in the U.S. was estimated to be a mere 5.7%. It has hovered around 5% for several years now, as we can see when we look at the last 10 years:

Notice anything interesting about the 10-year snapshot above? When times were hardest and we absolutely have to, what happened? Our savings rate was closer to 8%.

To me, that's why arguments about economic or political conditions only go so far. People love to play the blame game, citing all sorts of factors as to why it's "impossible" to save money. I will acknowledge that our economy and system isn't perfect and there are always improvements to be made - but extreme situations aside, this graph tells me that if we can save a higher amount when we're in a recession, then we can save a lot more when there's not.

Here's something else. Look at how other developed countries save money compared to us:

Source: HOWMUCH.NET

This isn't the time for a deep analysis on the economic and tax systems of each of these countries, but what I can say is this: those arguments would only go so far to explain the savings rate in each country. In the end, it is individuals making decisions to either save or spend their income as they receive it.

What concerns me about us in the U.S. is how quickly we've all come to adopt the 10% rule of thumb - not that many of us are actually keeping it. Many sources will tell you to give yourself a big pat on the back if you're saving 10% of your money. Looking at the data above, I suppose if you've got a 10% savings rate you're actually doing quite well compared to most people. But is that enough?

I'd like to suggest why I don't think saving 10% is enough in the context of three main financial goals most of us have.

SAVING 10% FOR AN EMERGENCY FUND

Let's start with what should be the most important immediate financial target for you if it's not in place already: an adequate emergency fund. We'll go with the oft-repeated advice to have an emergency fund equal to at least 3 months' living expenses.

With 63% of Americans saying they can't afford a $500 car repair or a $1,000 emergency room visit, I think it's safe to say that most people don't have sufficient emergency reserves, because a 3-month emergency fund for most people would be anywhere from $6,000 to $12,000.

Have you ever really thought about the math behind trying to save up an emergency fund while only having a 10% savings rate? Here's why saving only 10% may still not feel like it's getting you anywhere.

To make the math easy, let's say you have a $1,000 monthly income. If your savings rate is 10%, it means you save $100 per month. It also means your spending rate is 90%, or that your living expenses are $900 per month.

If you need a 3-month emergency fund, that means your goal should be to save up $900 x 3 months = $2,700.

The problem with that, of course, is that your savings rate is only $100 per month. That means it will take you 27 months to save up a 3-month emergency fund. And that's if you don't experience any emergencies along the way. How often do you go over two years without any sort of emergency?

Really, the single reason you can't get a sufficient emergency fund in place is because your rate of emergencies exceeds your rate of saving money.

So how fast can you save up an emergency fund at savings rates higher than 10%? I'll do the math for you:

If your savings rate is 15%, you will have a 3-month emergency fund in 17 months.

If your savings rate is 20%, it will only take you 12 months.

If your savings rate is 25%, it's a mere 9 months.

If your savings rate is 30% or higher, YOU'RE AWESOME. Take a bow.

SAVING 10% FOR A HOUSE DOWN PAYMENT

Another worthy goal of many is to buy a home. However, many of us are still operating under the "20% down payment" rule-of-thumb, which is, quite honestly, outdated. It was popularized about three decades ago when the proportion of wages to house prices were different, and when mortgage interest rates were over 10%. Brutal.

Since then, we've seen a steady increase in house prices while wages have stagnated. Do you realize what this means? For most people, you can't save 20% of a down payment in any realistic amount of time. Our incomes are much smaller in proportion to the cost of houses than 30 years ago.

So let's cross-examine another rule-of-thumb, the one that says "you can afford or should buy a house about three times your annual income."

How does the math turn out if you're trying to make a 20% down payment on a house three times your annual income?

If your savings rate is 10%, it will take you 6 years.

If your savings rate is 15%, it will take you 4 years.

If your savings rate is 20%, it will take you 3 years.

This decision is a complicated one. During the time you're waiting to buy because you're saving a down payment, will house prices continue to go up, or will there be a crash? Are mortgage interest rates going to go up?

Also, even if your savings rate is 10%, do you have an emergency fund in place yet? Are you going to save that up first?

As you can see, this creates another case for 10% savings taking a long time to get anywhere.

Yes, if you can save a 20% down payment, I say go for it. It will get you a lower interest rate and save you on private mortgage insurance, though there are ways to avoid that with less than 20% down. But it's not the worst thing to buy a house with less (I'd never put down less than 5% though). Trade-offs have to be made somewhere!

SAVING 10% FOR RETIREMENT

Okay, now it's time for the big kahuna. Retirement savings. The old advice goes something like this: "stuff 10% of your income into a 401(k) or any stock mutual fund for 40 years and you will have enough for retirement."

Hmm. That's a lot like saying "if you're in California, head eastward on the nearest interstate and set cruise control at 65 mph for 40 hours and you will end up in Washington DC." You might, and you might not. Instead, you'll end up closer to DC then you started, but most likely not where you have to be.

There are so many factors at play in a long-term wealth building effort that if the extent of your long-term financial plan for retirement is to "just put 10% somewhere", you're going to get a pretty vague result.

This old advice is rooted in the assumptions of a well-known (but perhaps outdated) study done in the 1990's that famously stated that you could withdraw 4% of your investment portfolio each year in retirement (increasing for inflation each year), and your portfolio will have a great chance of lasting at least 30 years. For example, if you started with $1 million you could withdraw $40,000 in the first year of retirement to live on and take out a little more for inflation each year thereafter.

A couple problems with that: life expectancies are now longer, and most economists forecast that the next 40 years are not going to have as high investment returns in the stock market as the last 40 years. This means that we may have to make up for it by saving more money than generations before us.

I'll dig deeper into why 10% can be an insufficient savings amount for retirement in a later article, but let me share just this for now: using this basic retirement calculator, I estimated that you'd have to work over 48 years to be able to live off of the 4% rule. That's a longer career than most people are planning on.

Source: Networthify

If you want to see how increasing your savings rate can dramatically affect your long-term future, see my earlier post about savings rates and early retirement.

Ultimately, what your savings rate should be depends completely on what your goals are! So you can't know how much you need to be saving unless you know what it is you want in your future. Do you want an early retirement? What kind of lifestyle do you want? Would you rather take a 1-2 year mid-life retirement or sabbatical, and work a little longer before fully retiring? Do you want to travel and have experiences, or are you more apt to buy your dream car or design your perfect house?

Whatever your financial goals are, in most cases you're going to need much more than a 10% savings rate to reach them.

A WORD OF ENCOURAGEMENT (AND A FEW TIPS)

I know that to many of you, hearing reasons why saving 10% of your money may be inadequate might be discouraging. Don't forget the statistics I mentioned at the beginning of this article - most people aren't saving 10% of their money. The majority of people already feel squeezed on their budget.

But my job as a financial planner is not to sugarcoat reality. It would be a disservice to validate socially accepted rules of thumb that are inadequate or misleading. My duty is to raise awareness and find creative solutions to work around it through investment and tax savings strategies.

However, no amount of investment or tax planning can make up for an inadequate savings rate. And remember that to save more money, you either 1) increase your income, 2) decrease your expenses, or 3) a combination of both.

The hardest part for people is not in understanding that, it's in implementing it. Most people expend all their energy cranking out the day-to-day grind that they don't have the time or mental space to proactively plan large efforts in these things.

All that being said, it's easy to feel stuck and like you'll never get to the savings rate you want. Starting small and slowly saving more and more sounds good in theory, but if you can make some large decisions more immediately, you'll feel a much bigger boost toward where you want to go financially.

A few tips to get started right away:

Automate your savings. Bypass your behavioral tendencies and make it go straight from your paycheck to your account. Don't leave it to yourself to put in whatever is left at the end of the month.

Make your savings inaccessible. If you have the tendency to "raid" the money you put in savings, it's time to make it harder to access. Put it in an account that's not the same bank or financial institution your checking account is with. Make it a non-online account, if you can find a place where that's possible.

Create accountability. Tell someone about your goal to save and ask them to make you stick to it. If you really want to get serious, ask your bank if they can create a joint account where you need all account holders' permission for withdrawal rights. Then, your accountability partner can talk sense in to you if you are trying to steal from your savings.

Beyond these little savings hacks, it may be that you need a "lifestyle gut check" like I wrote about in The 3 Real Ways to Cut Expenses. If you feel like you've reduced expenses as much as you can, then you may need to work on the other side of the equation - increasing your income. You might look for a side hustle or part-time job, start a small business, or learn salary negotiating skills for your next job review to bring home more bacon.

Less important than how you create a higher savings rate is that you just make it happen. So make it happen!